When a Bullet Silenced Obsession: The Story of George and the Future of Psychiatric Brain Interventions

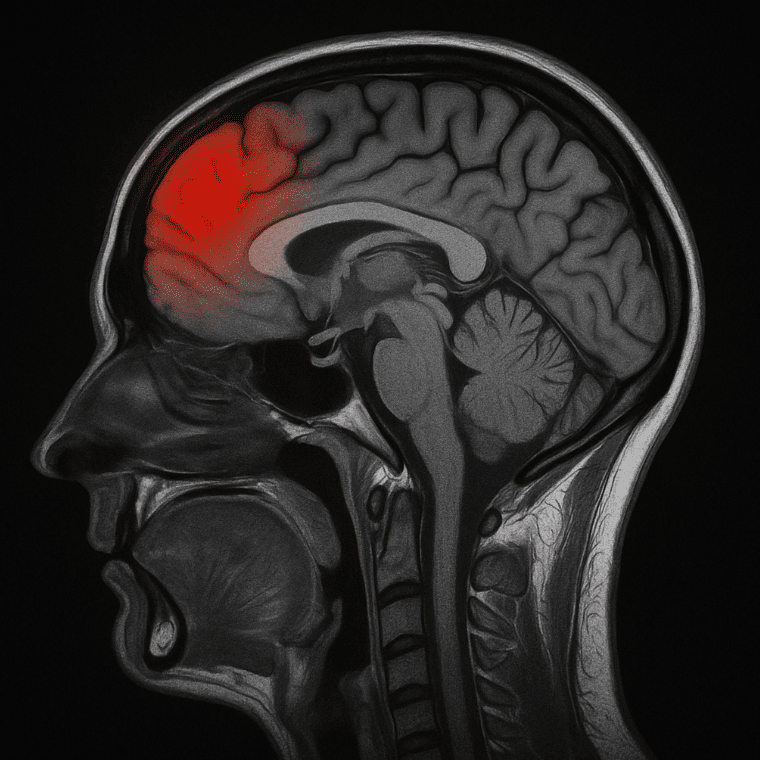

In 1988, the New York Times reported a case that continues to intrigue psychiatrists and neuroscientists alike: a young Canadian man with debilitating obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) accidentally “cured” himself after surviving a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. The bullet destroyed part of his frontal lobe—specifically, areas believed to mediate obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors.

In 1988, the New York Times reported a case that continues to intrigue psychiatrists and neuroscientists alike: a young Canadian man with debilitating obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) accidentally “cured” himself after surviving a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. The bullet destroyed part of his frontal lobe—specifically, areas believed to mediate obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors.

Remarkably, he not only survived but went on to complete college and lead a life free from the obsessive rituals that once plagued him. His case offers a rare window into the structural underpinnings of OCD and the evolving landscape of psychiatric neuromodulation and psychosurgery.

🧠 The Neuroanatomy of OCD: Which Brain Circuits Were Affected?

OCD is no longer seen as merely a “mental” illness. It is increasingly understood as a neurocircuitry disorder involving hyperactivity in specific brain loops, particularly the Cortico-Striato-Thalamo-Cortical (CSTC) circuit.

Key structures implicated:

-

Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC): Involved in error detection, decision-making, and reward expectation. Hyperactivity here may lead to an exaggerated sense of something being “not right.”

-

Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): Plays a role in emotional regulation and conflict monitoring.

-

Caudate Nucleus (part of the basal ganglia): Serves as a filter for information. Dysfunction can result in unchecked intrusive thoughts.

-

Thalamus: Acts as a relay; excessive input from the cortex can form a pathological feedback loop.

-

Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC): Involved in cognitive control and working memory. Modulating this region has shown promise in treatment-resistant OCD.

In George’s case, the bullet reportedly damaged parts of the frontal cortex, likely disrupting the overactive feedback loop in the OFC–striatum–thalamus axis. The sudden removal of a critical node in the circuit may have led to the cessation of his compulsive symptoms—a result eerily similar to targeted neurosurgical interventions.

⚡ From Lesions to Stimulation: The Rise of Neuromodulation

While George’s recovery was accidental and fraught with danger, today’s psychiatric medicine explores precise, reversible, and non-invasive ways to target similar brain areas.

1. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)

-

Mechanism: Uses magnetic pulses to modulate cortical excitability.

-

Target in OCD: Right DLPFC or Supplementary Motor Area (SMA); deeper coils now target the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex.

-

FDA Approval: In 2018, deep rTMS (using the H7 coil) received FDA clearance for OCD.

-

Clinical Use: 20–30 sessions over 4–6 weeks; often combined with CBT for synergistic effect.

-

Effect: Reduces obsessive thoughts by modulating fronto-striatal connectivity.

2. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

-

Mechanism: Delivers a low-level constant current via scalp electrodes.

-

Target: Typically anodal stimulation over DLPFC with cathodal over the supplementary motor area or orbitofrontal cortex.

-

Role in OCD: Evidence is still emerging, but promising in cases with emotional dysregulation or cognitive rigidity.

-

Advantages: Portable, painless, affordable—making it ideal for home-based or rural interventions.

🧬 Neurosurgery in Psychiatry: From Lobotomy to Precision Lesions

3. Cingulotomy and Capsulotomy

-

Anterior Cingulotomy: Aims to interrupt the cingulate cortex—a key hub in emotional salience and error monitoring. Reduces anxiety-driven obsessions.

-

Capsulotomy: Targets the internal capsule—particularly the anterior limb that links the frontal cortex to the thalamus.

-

Method: Performed via stereotactic radiosurgery or radiofrequency lesioning. Some centers now use MR-guided focused ultrasound.

-

Indication: Reserved for severe, treatment-resistant OCD where medication, therapy, and rTMS/tDCS fail.

-

Response Rate: ~30–60% response in carefully selected patients.

4. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

-

Mechanism: Implantable electrodes deliver continuous stimulation to deep brain targets.

-

Targets: Nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS), subthalamic nucleus.

-

FDA-HDE Approval: Granted for treatment-refractory OCD under Humanitarian Device Exemption.

-

Advantage: Adjustable and reversible—unlike permanent lesions.

-

Drawback: Invasive and expensive; requires lifelong monitoring.

🔄 The Ethical and Scientific Evolution

George’s case highlights both the plasticity and vulnerability of the human brain. His experience has echoes of historical cases—such as Phineas Gage (frontal trauma with personality change) and Henry Molaison (H.M.) (memory loss post-temporal lobectomy). But unlike them, George’s injury relieved psychiatric burden instead of causing it.

This paradox fuels our quest for minimally invasive, neurocircuit-based therapies that are targeted, ethical, and evidence-based. The shift from destructive to constructive modulation is the hallmark of modern psychiatric neuroscience.

🧭 Conclusion: From Serendipity to Science

What George’s case offered by accident, modern psychiatry now attempts with precision:

| Technique | Target Area | Invasiveness | Reversibility | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rTMS | DLPFC / SMA / OFC | Non-invasive | Yes | Moderate–severe OCD |

| tDCS | DLPFC / OFC | Non-invasive | Yes | Adjunct in mild–moderate OCD |

| Cingulotomy | Anterior cingulate cortex | Invasive | No | Treatment-resistant OCD |

| DBS | Nucleus accumbens, VC/VS | Invasive | Yes | Severe OCD |

George’s story is not a treatment model. But it was a clue—one that prompted deeper investigation into how brain regions create, maintain, and can sometimes silence mental illness.

The future lies in decoding these circuits further and finding the safest switches to reset them—not with bullets, but with science.