A New Insight into the Mechanism of Action of Stimulants in ADHD

Why medications like methylphenidate and amphetamines work very differently than we were taught

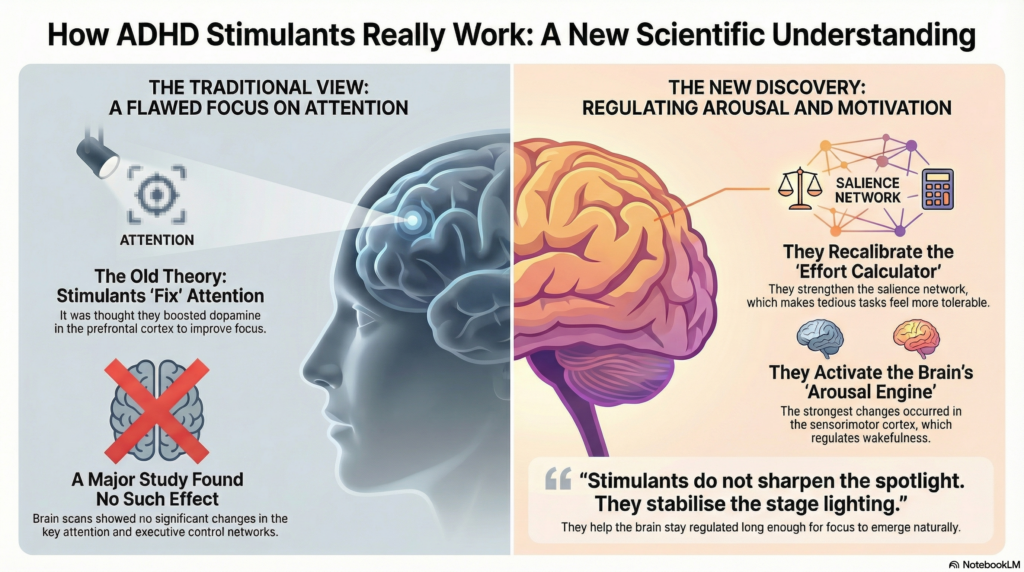

Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta), amphetamine salts (Adderall), and lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) are among the most commonly prescribed psychiatric medications worldwide. They have been used for decades, taught in medical schools as drugs that “improve attention” by acting on the brain’s executive control systems—particularly the prefrontal cortex.

A major neuroimaging study published in Cell now compels us to revise that explanation at a fundamental level.

The drugs work. But not by fixing attention.

The Traditional Explanation—and Its Cracks

Classic psychopharmacology describes stimulants as enhancing dopamine and noradrenaline signaling in the prefrontal cortex, thereby strengthening:

-

executive control

-

inhibitory capacity

-

sustained attention

This model became dogma. Yet several observations never fit comfortably:

-

Stimulants improve reaction time, persistence, and motivation more consistently than complex cognition

-

Benefits are largest in individuals performing poorly at baseline

-

High performers show little or no enhancement

-

Effects resemble those of adequate sleep and alertness

These inconsistencies hinted that attention itself might not be the primary target.

The Study That Changed the Frame

Led by Benjamin P. Kay with senior author Nico U. F. Dosenbach at Washington University School of Medicine, the study used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, one of the largest pediatric neuroimaging datasets ever assembled.

Key strengths of the study:

-

5,795 children, aged 8–11 years

-

Real-world stimulant use (primarily methylphenidate and amphetamine-based medications)

-

Resting-state functional MRI, not task-based scans

-

Whole-brain, data-driven connectome analysis

-

Rigorous control for motion, demographics, and socioeconomic variables

Instead of asking “Do stimulants activate attention areas?”, the researchers asked a more honest question:

“Which brain networks actually change when a child takes a stimulant?”

What the Researchers Did Not Find

Contrary to decades of teaching, stimulants produced no statistically significant changes in:

-

Dorsal attention network

-

Ventral attention network

-

Frontoparietal executive control network

These are the very circuits assumed to mediate attention, planning, and cognitive control.

This was not a subtle null result. Across thousands of scans, attention networks were essentially untouched.

Where Stimulants Do Act: Two Overlooked Systems

1. Sensorimotor Cortex – The Arousal Engine

The strongest and most consistent changes occurred in the sensorimotor cortex.

Traditionally labeled as a “movement” area, this region is now understood to play a central role in:

-

regulating wakefulness

-

maintaining tonic arousal

-

coordinating bodily readiness to act

Stimulants increased functional connectivity here, suggesting an elevation of baseline physiological alertness rather than sharper cognitive focus.

In plain terms:

The brain becomes more awake before it becomes more attentive.

2. Salience Network – The Effort–Reward Calculator

The salience network (anchored in the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex) determines:

-

what feels important

-

whether effort is worth expending

-

when to persist versus disengage

Stimulants strengthened connectivity between salience regions and motor systems. This suggests a recalibration of the brain’s effort–reward balance.

Tedious tasks—homework, lectures, sitting still—become less aversive.

Not more interesting. Just tolerable.

Why This Explains ADHD So Well

This model resolves several long-standing puzzles:

-

Why stimulants calm hyperactivity:

The drive to seek stimulation drops when internal reward needs are met. -

Why children can sit still without feeling trapped:

Motor restlessness decreases when arousal is adequately regulated. -

Why attention improves indirectly:

Attention emerges when engagement is sustained, not because attention circuits are “fixed.”

Stimulants do not sharpen the spotlight.

They stabilize the stage lighting.

The Sleep Discovery: Perhaps the Most Clinically Important Finding

The study uncovered a striking overlap between:

-

brain connectivity patterns in medicated children

-

patterns seen in well-rested children

Sleep deprivation disrupted the same arousal and sensorimotor networks affected by stimulants.

When sleep-deprived children took stimulants:

-

the “sleep-loss brain signature” disappeared

-

cognitive and academic performance normalized

Importantly:

-

Well-rested children without ADHD showed no performance benefit

-

Stimulants did not enhance already optimal brains

This strongly suggests that stimulants act as pharmacological wakefulness, not cognitive enhancement.

A Warning Embedded in the Data

While stimulants can mask sleep deprivation, they do not replace sleep.

Chronic sleep loss carries:

-

metabolic consequences

-

neurodevelopmental stress

-

emotional dysregulation

The medication hides the signal but does not repair the damage.

This has direct diagnostic implications:

Sleep deprivation can look indistinguishable from ADHD.

Rethinking ADHD: From Attention to State Regulation

This study supports a growing reconceptualization of ADHD as a disorder of:

-

arousal regulation

-

effort allocation

-

motivational stability

Attention problems may be secondary—downstream effects of unstable internal states.

The involvement of the motor system aligns with emerging ideas such as the Somato-Cognitive Action Network, integrating movement, arousal, and planning into a single functional loop.

What This Means for Practice

-

Screening for sleep problems is not optional

-

Behavioral and lifestyle interventions target the same biology as medication

-

Stimulants are best understood as endurance tools, not “smart drugs”

-

Expectations should shift from “improving attention” to “supporting sustained engagement”

Closing Reflection

This study does not diminish stimulant medications—it clarifies them.

They do not teach the brain how to focus.

They help the brain stay awake, motivated, and regulated long enough for focus to happen.

That distinction reshapes how we diagnose, prescribe, and explain ADHD—bringing neuroscience closer to what clinicians and patients have quietly observed all along.