Childhood OCD: Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in childhood is frequently misunderstood, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Often dismissed as “just a phase,” stubbornness, or perfectionism, Childhood OCD is in reality a neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorder that can significantly disrupt emotional, cognitive, and social development if not recognised early.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in childhood is frequently misunderstood, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Often dismissed as “just a phase,” stubbornness, or perfectionism, Childhood OCD is in reality a neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorder that can significantly disrupt emotional, cognitive, and social development if not recognised early.

Research consistently shows that nearly half of all OCD cases begin in childhood or adolescence, with a peak onset between 10 and 12 years of age. Childhood-onset OCD differs meaningfully from adult-onset OCD—in clinical presentation, comorbidities, neurobiology, and long-term outcomes—making early identification both challenging and crucial.

Why Childhood OCD Is Difficult to Diagnose

Limited Insight and Expression

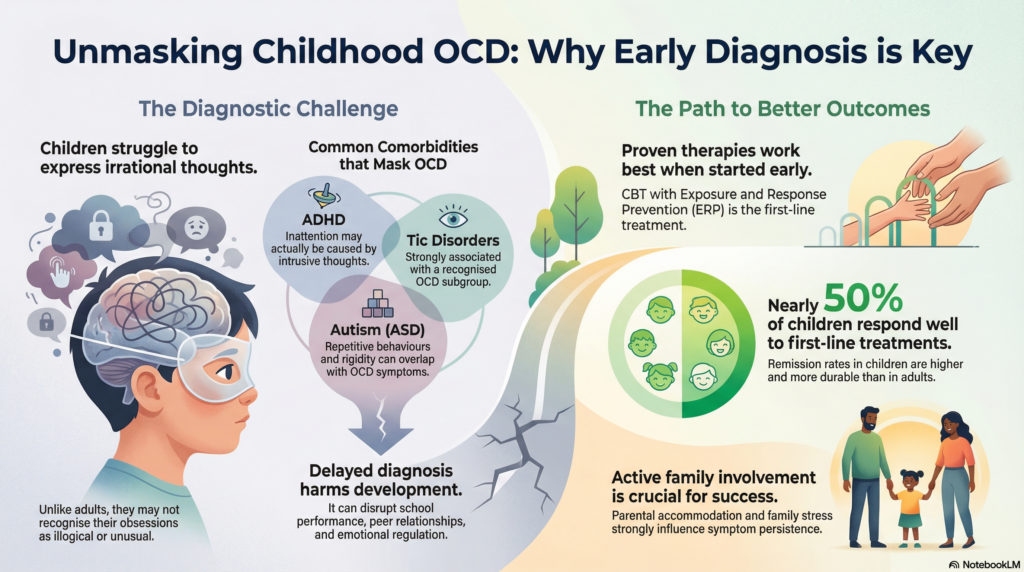

Unlike adults, children often do not recognise obsessions as irrational. Intrusive thoughts may feel realistic, morally significant, or necessary. Many children struggle to verbalise these experiences, leading to misinterpretation by parents and clinicians as anxiety, oppositional behaviour, or attention problems.

The Subclinical Overlap

Studies suggest that 10–15% of children experience subclinical obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Rituals, repetitive questioning, reassurance seeking, and rigid routines can overlap with normal developmental behaviours, especially in younger children. This overlap frequently results in a delayed diagnosis and prolonged duration of untreated illness.

Comorbidity: The Diagnostic Chameleon

Childhood OCD rarely presents in isolation and is commonly masked by co-occurring neurodevelopmental conditions:

-

ADHD: Present in approximately 20% of children with OCD. Apparent inattention may reflect intrusive thoughts rather than a primary attentional deficit.

-

Tic disorders: Strongly associated with a recognised subgroup known as Obsessive-Compulsive Tic Disorder (OCTD).

-

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Overlapping features such as rigidity, repetitive behaviours, and sensory sensitivities complicate diagnosis and require tailored interventions.

Developmental Consequences of Delayed Diagnosis

Delayed recognition is not benign. A longer duration of untreated illness (DUI) is associated with academic disruption, impaired peer relationships, emotional dysregulation, and entrenched cognitive styles that may persist into adulthood.

Challenges in Treating Childhood OCD

Standard Treatments Work—But Timing Matters

The cornerstone of treatment remains evidence-based and effective when applied early:

-

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) with Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) is first-line for mild to moderate cases.

-

Combination therapy (CBT + SSRIs) is recommended for moderate to severe OCD.

However, delayed treatment often means higher symptom severity, greater family accommodation, and slower response rates.

Neurodevelopmental and Biological Complexity

Emerging research highlights that childhood OCD is not solely a serotonin disorder:

-

Glutamatergic dysregulation plays a significant role, prompting interest in adjunctive agents such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and memantine for treatment-resistant cases.

-

Immune and inflammatory mechanisms are particularly relevant in abrupt-onset presentations such as PANS/PANDAS, where immunological interventions may be indicated.

-

Gut–brain axis influences during sensitive periods of brain development suggest future roles for microbiome-focused interventions.

These findings mark a shift toward precision psychiatry, where treatment is individualised rather than uniform.

Why Early Intervention Changes Outcomes

One of the most hopeful aspects of childhood OCD is prognosis. Remission rates in children are higher and more durable than in adults, with nearly 50% responding well to first-line treatments.

Key factors that improve outcomes include:

-

Early screening, especially in children presenting with anxiety, tics, or attentional difficulties.

-

Treating OCD first when ADHD and OCD coexist, as reducing obsessions can secondarily improve attention.

-

Active family involvement, as parental accommodation and family stress strongly influence symptom persistence.

Conclusion

Childhood OCD is a multidimensional neurodevelopmental disorder, not a minor behavioural issue or personality trait. The challenges in diagnosis stem from developmental factors, symptom overlap, and comorbidity, while treatment complexity reflects underlying biological diversity.

Early recognition and timely, developmentally informed intervention can dramatically alter a child’s trajectory—protecting academic progress, emotional development, and long-term mental health. The goal is not merely symptom reduction, but preserving developmental momentum and psychological resilience.

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS, New Delhi)

Consultant Psychiatrist

Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808

Related posts:

- Adult ADHD: Assessment, Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment

- Childhood Violence: Recognizing and Addressing Aggressive Behaviors

- Autism Across the Lifespan: From Childhood to Adulthood

- How Was Your Childhood? This 3-Minute Test Might Explain a Lifetime of Struggles

- Childhood Trauma: Therapy and Recovery from PTSD

- 🧠 OCD and Tics: Non-Medical Treatment Strategies for Better Control