How Brain Function Differs in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

A Neurobiological Perspective Beyond “Deficits”

A Neurobiological Perspective Beyond “Deficits”

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is often discussed in terms of observable behaviour—social difficulties, sensory sensitivity, restricted interests, and rigid routines. While these features are real and clinically important, they are only the surface expression of deeper neurobiological differences in brain organisation and information processing.

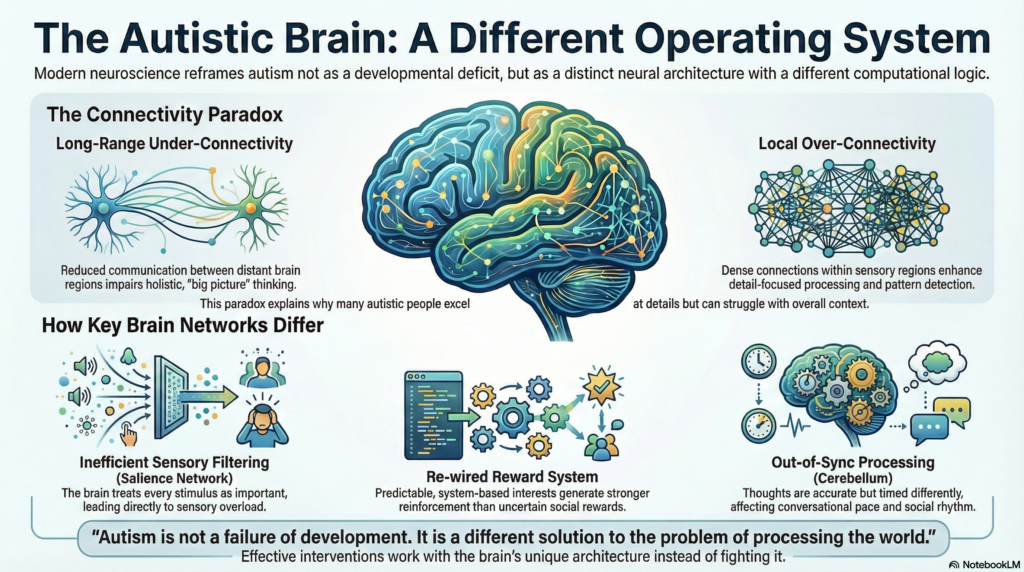

Modern neuroscience no longer frames autism as a simple developmental “deficit.” Instead, ASD represents a distinct neural architecture—a brain that follows a different computational logic rather than a broken one.

Understanding this shift is crucial for accurate diagnosis, compassionate care, and effective intervention.

Autism as a Disorder of Brain Connectivity

One of the most consistent findings in autism research is atypical brain connectivity. Rather than a uniform increase or decrease in connections, ASD shows a connectivity imbalance, often referred to as the connectivity paradox.

Long-Range Under-Connectivity

Communication between distant brain regions—particularly frontal areas (planning, regulation, social cognition) and posterior sensory regions—is reduced. This affects global integration of information, especially in complex social contexts.

Local Over-Connectivity

At the same time, local circuits—especially within sensory and perceptual regions—are densely connected. This enhances detail-focused processing, pattern detection, and systemisation.

Clinical implication:

This explains why many autistic individuals excel at details yet struggle with holistic interpretation. Behaviour often labelled as “rigid” is frequently an adaptive response to managing overwhelming, poorly integrated input.

The Salience Network: Why Sensory Overload Happens

The Salience Network (SN) acts as the brain’s filter, deciding what deserves attention and what can be ignored.

In ASD, this system often shows hyper-connectivity and inefficient filtering, leading to:

-

Sensory overload

-

Difficulty prioritising social cues

-

Excessive bottom-up attention

The brain becomes biologically compelled to treat every stimulus as important. Background noise, bright lights, or subtle sensory changes compete for attention as if they were threats.

This is why autistic individuals may say:

“I can’t concentrate because the light is too loud.”

This is not metaphorical—it reflects how the brain is processing sensory input.

Cerebellar Differences and the “Timing” of Thought

The cerebellum, traditionally associated with motor coordination, plays a critical role in timing, prediction, and cognitive fluidity.

In ASD, cerebellar differences lead to what researchers describe as “dysmetria of thought.” Information processing is accurate—but poorly synchronised.

This manifests as:

-

Delayed conversational timing

-

Difficulty keeping pace with social exchanges

-

A feeling of being “out of sync”

Many individuals articulate this as:

“I know what to say, but I can’t get the timing right.”

Social difficulty here is not a lack of understanding, but a temporal processing delay.

Reward System Re-Wiring in Autism

The brain’s reward circuitry—particularly the ventral striatum—responds differently in ASD.

In neurotypical brains, social approval and interpersonal feedback strongly activate reward pathways. In autism:

-

Social rewards often produce a weaker dopaminergic response

-

Predictable, system-based interests generate stronger reinforcement

This is not avoidance of people—it is a biologically re-prioritised reward system that favours low-entropy, predictable inputs over complex social uncertainty.

Special interests, therefore, function as stabilising anchors rather than mere obsessions.

Amygdala, Prefrontal Cortex, and Cognitive Load

Research also points to:

-

Slower amygdala habituation to social stimuli

-

Reduced efficiency in prefrontal regulatory networks

As a result, tasks such as face processing, emotional interpretation, and social decision-making require significantly more cognitive effort.

Social interaction becomes mentally exhausting, explaining why withdrawal often reflects neural fatigue, not disinterest or oppositionality.

Translating Neurobiology Into Clinical Care

Understanding mechanisms allows interventions to become targeted rather than generic.

-

Sensory overload: sensory optimisation, environmental modification, bottom-up regulation

-

Processing delay: explicit communication, structured conversations, predictable templates

-

Reward differences: interest-led engagement and motivation

-

Cognitive rigidity: transition anchors, if–then planning, advance signalling

These approaches work with the brain’s architecture instead of fighting it.

Reframing Autism in Clinical Practice

Autism is not a failure of development.

It is a different solution to the problem of processing the world.

When clinicians shift from asking “What is this person not doing?” to “What is this brain optimised for?”, care becomes more precise, humane, and effective.

This reframing is not just philosophical—it directly improves outcomes.

Final Thought

Precision psychiatry begins when we understand the brain behind the behaviour. Autism reminds us that difference does not imply deficiency—only diversity in neural design.

👨⚕️ About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA

Consultant Psychiatrist

Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall), Chennai

I work at the intersection of clinical psychiatry, neuroscience, and neurotechnology, with a special interest in autism, ADHD, neurofeedback, and precision-based mental healthcare.

📧 srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808

🌐 srinivasaiims.com

For evaluations, consultations, or professional collaborations, feel free to reach out.