Priming the Brain During tDCS: How Cognitive Tasks Shape Neuroplasticity

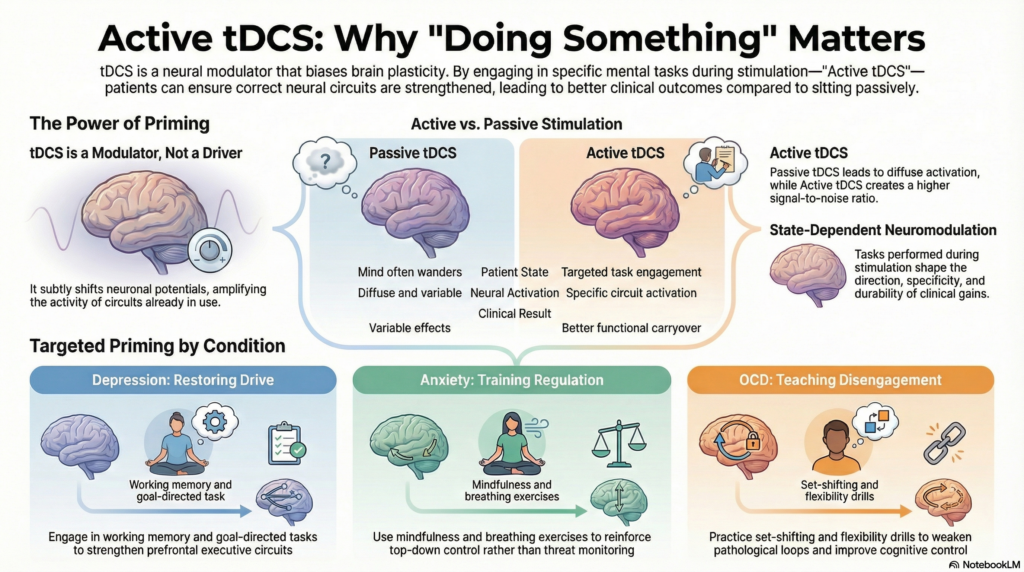

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) is often described as a mild electrical intervention that “stimulates” the brain. This description is convenient, but it misses the central mechanism that actually determines whether tDCS helps a patient or quietly fails.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) is often described as a mild electrical intervention that “stimulates” the brain. This description is convenient, but it misses the central mechanism that actually determines whether tDCS helps a patient or quietly fails.

tDCS does not work because electricity is applied.

It works because neuroplasticity is temporarily enhanced.

And neuroplasticity, by definition, is experience-dependent.

This is why the question that matters most during tDCS is not how much current or even where the electrodes are placed, but something far more fundamental:

What is the brain doing while it is most ready to change?

Neuroplasticity Is the Treatment, tDCS Is the Facilitator

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganize synaptic connections based on activity and learning. In psychiatric disorders, plasticity often becomes either insufficient (as in depression) or maladaptive (as in anxiety and OCD).

tDCS works by subtly shifting neuronal membrane potentials, making neurons more or less likely to fire. This does not impose new activity. Instead, it lowers the threshold for plastic change in networks that are already active.

In simple terms, tDCS opens a learning window.

Cognitive tasks decide what is learned.

This principle—known as state-dependent neuromodulation—is not theoretical. It is embedded in how many of the most influential tDCS studies are designed.

Why Passive tDCS Is a Missed Opportunity

When patients sit quietly during stimulation, the brain does not switch off. It defaults.

For many psychiatric patients, the default state is:

-

Rumination in depression

-

Hypervigilance in anxiety

-

Obsessive loops in OCD

tDCS applied during these states risks reinforcing the very networks we are trying to weaken. Passive tDCS is therefore not neutral—it is unguided plasticity.

Active tDCS introduces intentional cognitive engagement, steering plastic change toward adaptive networks.

What Tasks Do Researchers Actually Use?

A striking feature of the literature is that task pairing is not random. Across disorders, researchers repeatedly choose tasks that reliably activate the neural bottleneck relevant to that condition.

Let’s look at what is actually used.

Depression: Training Cognitive Control Over Rumination

Depression is increasingly understood as a disorder of impaired prefrontal plasticity, particularly in networks responsible for motivation, executive control, and disengagement from negative thought patterns.

Cognitive Control Training (PASAT and adaptive PASAT)

One of the most commonly used tasks paired with tDCS in depression studies is the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT) or its adaptive variants.

This task requires continuous updating, sustained attention, error tolerance, and resistance to emotional frustration—exactly the capacities weakened by depressive rumination.

Studies pairing tDCS with PASAT-based training show:

-

Better long-term antidepressant effects

-

More durable cognitive gains

-

Superior outcomes compared to tDCS or training alone

The rationale is clear: tDCS enhances plasticity in prefrontal control circuits, while PASAT teaches those circuits how to function again.

Working Memory Tasks (N-back)

Another frequently used task is the N-back working memory paradigm, especially at higher loads (2-back or 3-back).

N-back tasks robustly engage the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and require:

-

Updating

-

Monitoring

-

Inhibition of irrelevant information

Studies show that task difficulty matters. Higher cognitive demand during stimulation produces more consistent effects—reinforcing the idea that tDCS amplifies active learning rather than passively “boosting” cognition.

Emotional Cognitive Training

Some trials extend this logic by using emotional variants of working memory tasks, where patients must maintain cognitive performance while ignoring emotionally salient distractors.

Here, the aim is not just cognitive strengthening, but training control over emotional interference, a core deficit in depression.

Anxiety Disorders: Plasticity Through Regulation, Not Arousal

Anxiety disorders are often associated with overtrained threat circuits and poor inhibitory control. Simply exciting the prefrontal cortex without guidance risks worsening symptoms.

Accordingly, researchers pair tDCS with tasks that emphasize regulation and extinction learning.

Mindfulness and Focused Attention Tasks

Several studies combine tDCS with structured mindfulness or focused-attention exercises, sometimes even during movement (such as mindful walking).

These tasks engage:

-

Sustained attention

-

Reorientation after distraction

-

Decentering from threat

When paired with stimulation, the goal is not sedation, but plastic reinforcement of regulatory control.

Exposure-Based Tasks

In fear-based anxiety disorders, the task during stimulation is often exposure itself.

Whether conducted in vivo or through virtual reality, exposure is a form of plasticity training: repeated prediction error teaches the brain that threat responses are no longer necessary.

tDCS during exposure appears to enhance extinction learning, not by suppressing fear, but by strengthening learning circuits that encode safety.

OCD: Training Inhibition and Cognitive Flexibility

OCD is best understood as a disorder of pathological overlearning. Circuits governing doubt, checking, and control become rigid and resistant to disengagement.

tDCS studies in OCD frequently target medial frontal and pre-SMA regions and pair stimulation with inhibition-heavy cognitive paradigms.

Inhibitory Control Tasks (Stroop, Stop-Signal)

Tasks such as the Stroop test are not merely outcome measures—they reflect the cognitive bottleneck researchers aim to modify.

These tasks require:

-

Suppression of prepotent responses

-

Conflict monitoring

-

Flexible switching

When paired with stimulation, they help retrain networks responsible for stopping, shifting, and disengaging, capacities that are compromised in OCD.

Cognitive Flexibility Tasks

Some protocols emphasize set-shifting and reversal learning, reinforcing the brain’s ability to let go of rigid rules and tolerate uncertainty.

tDCS does not erase obsessions. Paired with these tasks, it weakens compulsive urgency by restoring flexibility.

Why These Tasks—and Not Others—Work

Across disorders, successful task pairing shares three features:

-

Network specificity – tasks reliably activate the intended circuit

-

Sufficient challenge – plasticity follows effort, not ease

-

Clinical relevance – tasks mirror real-world deficits

This is why generic puzzles or passive activities are unlikely to help. Plasticity follows meaningful demand, not distraction.

QEEG and Task Selection: Precision Plasticity

QEEG adds another layer of sophistication by identifying:

-

Hypoactive networks needing facilitation

-

Hyperactive networks requiring inhibition

-

Poorly regulated state transitions

This allows clinicians to choose not just the stimulation target, but the cognitive task most likely to drive adaptive plasticity in that network.

The model becomes:

QEEG → Target → Task → Plastic Change

Reframing Active tDCS: Guided Learning, Not Electrical Treatment

tDCS should not be thought of as a treatment that acts on the brain. It acts with the brain.

Cognitive tasks are not optional extras. They are the training signal that tells the plastic brain what to become better at.

Electrodes create opportunity.

Tasks provide direction.

Neuroplasticity does the work.

Final Thoughts: Why Active tDCS Is the Way Forward

Active tDCS respects a fundamental truth of neuroscience:

The brain changes according to what it practices, especially when plasticity is enhanced.

When we pair stimulation with carefully chosen cognitive tasks, we stop hoping for nonspecific effects and start teaching networks how to function again.

That is not just better neuromodulation.

It is better, more honest psychiatry.

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS, New Delhi), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery

📞 +91-8595155808