Sleep Isn’t Just About Hours: Why Patterns Matter More Than We Think

Most people think about sleep in one dimension:

Most people think about sleep in one dimension:

How many hours did I sleep?

It’s a neat, comforting number. Trackable. Comparable. Easy to brag—or worry—about.

But biology has never been impressed by neat numbers.

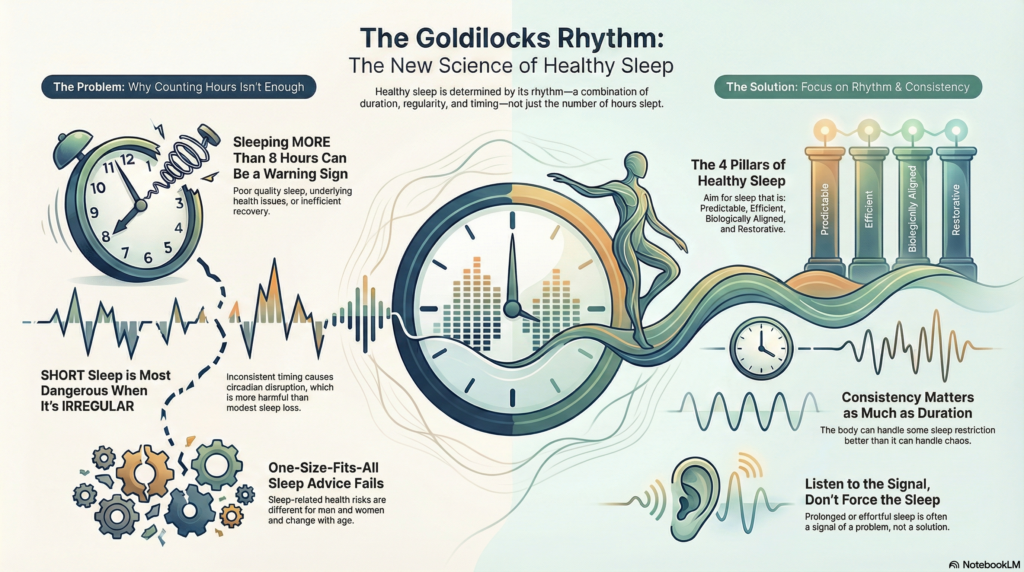

A growing body of research now suggests that sleep is not a single variable, but a pattern—a rhythm shaped by duration, regularity, and alignment with our internal clock. And when that rhythm is disturbed, the consequences can extend far beyond fatigue or poor concentration.

A large, long-term population study published recently adds important nuance to how we should think about sleep, health, and longevity.

The Goldilocks Zone Still Exists—But It’s Narrower Than We Thought

For years, the advice has been consistent: 7–8 hours of sleep per night is associated with the best health outcomes.

That still holds true.

People who habitually slept in this range had the lowest risk of death over long-term follow-up. But what’s striking is what happens outside this window—and why.

When Sleeping Too Much Is Not a Good Sign

Sleeping more than 8 hours regularly was associated with a higher risk of death, even after accounting for age, medical conditions, lifestyle factors, and socioeconomic status.

This finding often surprises patients. After all, isn’t more rest better?

Not necessarily.

Long sleep may reflect:

-

Fragmented or poor-quality sleep

-

Underlying medical or sleep disorders

-

Reduced physiological resilience

-

A body compensating for inefficient recovery

In older adults, this association was especially strong. In other words, prolonged sleep may sometimes be a marker of vulnerability rather than vitality.

Short Sleep Becomes Dangerous When It’s Irregular

Short sleep—less than 7 hours—has long been associated with health risks. But this study reveals an important distinction:

Short sleep by itself was not the biggest problem.

Short sleep combined with irregular timing was.

People who slept fewer hours and had inconsistent bedtimes and wake times showed a significantly higher risk of death.

This points to something deeper than sleep deprivation: circadian disruption.

When sleep timing is unpredictable, the brain and body struggle to coordinate:

-

Hormone release

-

Autonomic balance

-

Glucose metabolism

-

Inflammatory control

The body can tolerate modest sleep restriction far better than it can tolerate chaos.

Men and Women Don’t Respond the Same Way

One of the most clinically meaningful insights from this research is that sleep-related risks differ by sex.

In men

Short sleep combined with irregular timing carried higher risk. Long sleep, even when regular, was also associated with increased mortality—possibly reflecting work stress, sleep apnea, or fragmented recovery.

In women

The strongest risk appeared in those with long and irregular sleep, who also showed higher cardiovascular event risk. Hormonal transitions, caregiving demands, and insomnia-related fatigue may all play a role.

The takeaway is simple but often ignored:

Sleep advice cannot be one-size-fits-all.

Age Changes the Equation Too

Sleep biology evolves across the lifespan.

-

In middle-aged adults, shorter sleep appeared more harmful

-

In older adults, prolonged sleep carried greater risk

Younger bodies struggle more with deprivation. Older bodies struggle more with inefficiency and fragmentation.

Why This Matters in Everyday Practice

Most people still receive sleep advice that sounds like a slogan:

“Just get 7–8 hours.”

This research suggests a better message:

-

Consistency matters as much as duration

-

Longer sleep is not always healthier

-

Irregular sleep is a silent risk factor

-

Sleep patterns must be interpreted in context

This is also why approaches that focus on sleep timing, regularity, and efficiency, such as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), often outperform medication-based approaches over time.

Good sleep is not about chasing hours in bed.

It’s about restoring rhythm.

A Better Way to Think About Sleep

Healthy sleep looks less like “more” or “less” and more like:

-

Predictable

-

Efficient

-

Biologically aligned

-

Restorative rather than compensatory

When sleep becomes prolonged, irregular, or effortful, it’s often a signal—not a solution.

Listening to that signal early may be one of the simplest ways to protect long-term health.

Reference

Park SJ, Park J, Kim BS, Park J-K. The impact of sleep health on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population. Scientific Reports. 2025;15:30034.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS, New Delhi)

Consultant Psychiatrist

Dr. Srinivas works at the intersection of psychiatry, sleep science, and behavioural medicine. His clinical focus includes evidence-based management of insomnia using CBT-I, circadian rhythm optimisation, and treatment of sleep disturbances associated with anxiety, depression, ADHD, and medical illness.

He regularly writes on sleep, mental health, and neurobiology to bridge the gap between research and real-world clinical care.

📍 Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808