Sleep Series: Beyond Eight Hours — Rethinking Sleep, Rhythm, and Health

Sleep Isn’t Just About Hours: Why Patterns Matter More Than We Think

Sleep Isn’t Just About Hours: Why Patterns Matter More Than We Think

Ask someone how their sleep is, and you’ll almost always get a number in response.

“Six hours.”

“Barely five.”

“I sleep eight hours, but I’m still tired.”

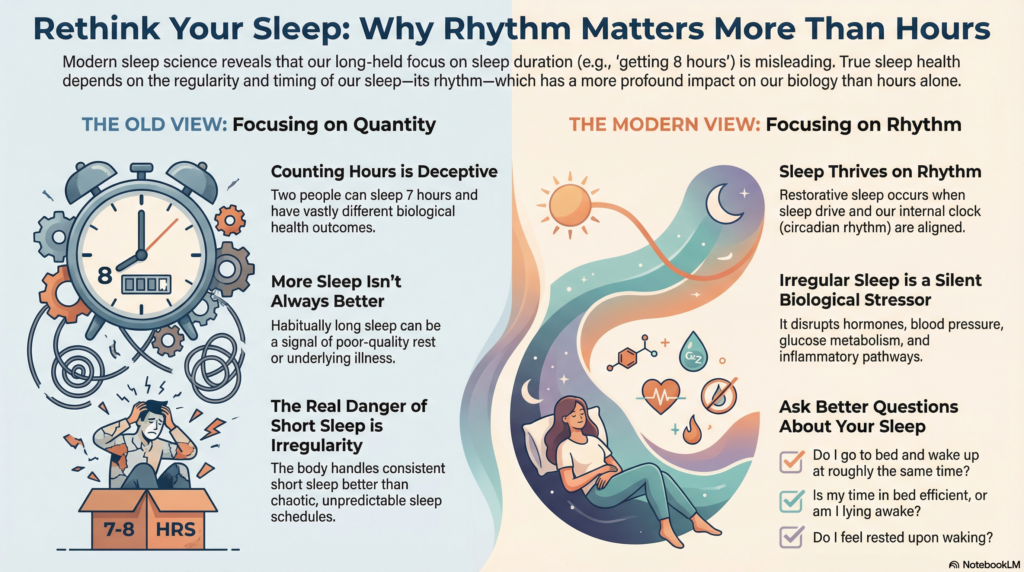

We have trained ourselves to think of sleep as a quantity—something that can be measured, optimized, and compared like steps on a fitness tracker. And for a long time, medicine encouraged this way of thinking. Seven to eight hours became the magic range. Less was bad. More was assumed to be better.

But biology, as it turns out, doesn’t care much for tidy slogans.

Recent large-scale research is forcing us to rethink sleep not as a single number, but as a pattern—a rhythm shaped by duration, regularity, and alignment with our internal clock. And when that rhythm is disturbed, the consequences reach far beyond grogginess or poor concentration. They may affect long-term health and even survival.

The Problem With Asking Only “How Many Hours?”

Two people can both report sleeping seven hours and have completely different sleep health.

One goes to bed and wakes up at roughly the same time every day, falls asleep easily, and feels reasonably refreshed.

The other sleeps at wildly different times, lies awake for long stretches, extends time in bed to “compensate,” and wakes up exhausted.

On paper, the hours look identical. Biologically, they are not even close.

Sleep is regulated by two powerful systems:

-

Sleep drive, which builds the longer we stay awake

-

Circadian rhythm, our internal clock that expects sleep and wakefulness at predictable times

When these systems are aligned, sleep tends to be efficient and restorative. When they are not, simply spending more time in bed does not fix the problem—and may even worsen it.

When More Sleep Is Not Always Healthier

One of the most counterintuitive findings from recent population studies is that habitually sleeping longer than eight hours is not automatically protective. In fact, in many adults—especially older adults—it is associated with higher health risk.

This does not mean that sleep itself is harmful. It means that long sleep is often a signal, not a solution.

Prolonged sleep can reflect:

-

Fragmented or poor-quality sleep

-

Repeated nighttime awakenings

-

Medical or psychiatric illness

-

Reduced physiological resilience

In such cases, the body stretches sleep time in an attempt to recover—but the recovery remains inefficient. The result is more time in bed, not better rest.

Short Sleep Becomes Dangerous When It Is Irregular

Short sleep has long been linked to health problems, but the picture is more nuanced than “less sleep equals more risk.”

What seems to matter most is regularity.

People who sleep fewer hours but maintain consistent bedtimes and wake times often fare better than those whose sleep timing is chaotic. Irregular sleep disrupts circadian rhythms, leading to mismatches between when the brain expects sleep and when it actually occurs.

This circadian disruption affects:

-

Hormonal regulation

-

Blood pressure and heart rate

-

Glucose metabolism

-

Inflammatory pathways

The body can adapt to modest sleep restriction far better than it can adapt to unpredictability.

Why This Changes How We Should Think About Sleep

For years, sleep advice has sounded deceptively simple:

“Get seven to eight hours.”

What modern evidence suggests is something more precise—and more realistic:

-

Consistency matters as much as duration

-

More sleep is not always better sleep

-

Irregular sleep is a silent biological stressor

-

Sleep problems are often about timing, not just quantity

This also explains why approaches that focus on restoring rhythm—rather than forcing sedation—tend to work better over time. Sleep improves when the brain relearns when to sleep, not when it is merely switched off.

A Better Question to Ask

Instead of asking only:

“How many hours did I sleep?”

A better starting point might be:

-

Do I sleep at roughly the same time each night?

-

Is my time in bed efficient, or am I lying awake for long periods?

-

Do I feel rested, or am I compensating with longer sleep?

-

Is my sleep predictable—or constantly shifting?

Sleep is not passive rest. It is an active biological process that thrives on rhythm.

And when that rhythm is disturbed, the solution is rarely “more hours.” It is better alignment.

This series will explore what that alignment looks like—across age, gender, lifestyle, and clinical conditions—and why restoring sleep rhythm may be one of the most powerful, underestimated tools for long-term health.

Reference

Park SJ, Park J, Kim BS, Park J-K. The impact of sleep health on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population. Scientific Reports. 2025;15:30034.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Dr. Srinivas works at the intersection of psychiatry, sleep science, and behavioural medicine, with a special focus on evidence-based treatments for insomnia, circadian rhythm disturbances, anxiety, depression, and ADHD. He regularly uses Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) and rhythm-based interventions to help patients achieve durable, medication-sparing sleep improvement.

📍 Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall), Chennai

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808