The Borderline Mother and the Making of the Borderline Self: Insights from James F. Masterson

Introduction

Introduction

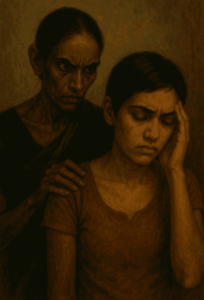

In the complex landscape of personality development, few theorists have provided as rich and clinically grounded a model as James F. Masterson, whose work on the Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) remains a cornerstone in psychodynamic psychiatry. Among his most provocative ideas is the notion that the mother of a borderline patient often carries borderline traits herself. This is not merely a comment on heredity, but rather on the deep, unconscious interpersonal dynamics that shape the child’s developing self.

The Borderline Dilemma: A Developmental View

At the heart of Masterson’s theory is the failure of the separation-individuation process, a crucial developmental stage described by Margaret Mahler. Ideally, as a child grows, the caregiver gradually supports the child’s moves toward autonomy while maintaining a secure emotional connection. In borderline pathology, this process goes awry.

Masterson observed that borderline mothers oscillate between engulfment and abandonment. They cling to the child for emotional support, fearing their own inner emptiness, yet punish or withdraw from the child when the child asserts autonomy. This erratic pattern teaches the child a painful lesson:

“If I try to be myself, I lose love. If I give up myself to keep love, I lose my true self.”

Thus, the child internalizes a split sense of self: one part compliant and dependent (to secure the mother’s love), the other angry, empty, and yearning for freedom (but terrified of abandonment). This inner conflict crystallizes into the unstable self-structure characteristic of BPD.

Profile of the Borderline Mother

While Masterson was careful not to suggest that all mothers of borderline individuals have BPD, he highlighted a pattern of borderline traits commonly observed:

-

Emotional volatility: Shifting rapidly between idealization and devaluation of the child.

-

Fear of abandonment: Clinging to the child as an extension of herself.

-

Manipulation through guilt or withdrawal: Using emotional leverage to maintain control.

-

Fragile self-esteem: Dependent on the child’s responsiveness.

Such a mother is often unconsciously driven by her own unresolved developmental wounds and uses the child to stabilize her sense of self, perpetuating the cycle.

Clinical Implications

For therapists, understanding this intergenerational transmission of pathology is crucial. The borderline patient’s intense fears of abandonment, chronic feelings of emptiness, and oscillations between idealization and devaluation are rooted in early relational templates. Therapy must gently address the internalized “borderline mother” within the patient’s psyche, helping them:

-

Mourn the lack of a secure early attachment.

-

Develop a more integrated, realistic sense of self.

-

Learn new ways of relating that do not replicate past patterns.

Therapists must also remain vigilant to countertransference reactions, as the therapist may unconsciously be pulled into the same split dynamics the patient experienced with the mother.

A Word of Caution

This theory should not be misused to blame mothers simplistically. Masterson’s contribution is not about fault-finding, but about understanding how disturbed attachments shape psychic structures. Many of these mothers carry their own histories of trauma and deprivation, often across generations.

Conclusion

Masterson’s insight into the borderline mother-child dyad provides a powerful lens for clinicians to understand the origins of borderline pathology. The pathway to healing lies in recognizing these early wounds, not perpetuating blame, and in helping patients reconstruct a stable, cohesive sense of self capable of genuine intimacy and autonomy.