Understanding Antidepressants and Withdrawal: A Neurobiological + Phenomenological Approach

Most debates about antidepressants fall into two extremes.

Most debates about antidepressants fall into two extremes.

One side talks only about brain chemistry and receptors.

The other side talks only about lived experience and suffering.

Both are incomplete.

To truly understand how antidepressants work — and what happens when they are stopped — we need both:

-

a neurobiological lens (what the drug does to the brain)

-

a phenomenological lens (what the person actually experiences)

When these two are combined, confusion drops, fear reduces, and treatment becomes far more humane and effective.

What antidepressants actually do to the brain

Antidepressants do not simply “add serotonin.”

Over weeks to months, they produce adaptive changes across multiple brain systems.

These include:

-

changes in serotonin receptor sensitivity

-

altered noradrenaline and dopamine signalling

-

reduced amygdala threat reactivity

-

changes in stress-hormone regulation

-

altered sleep architecture (especially REM sleep)

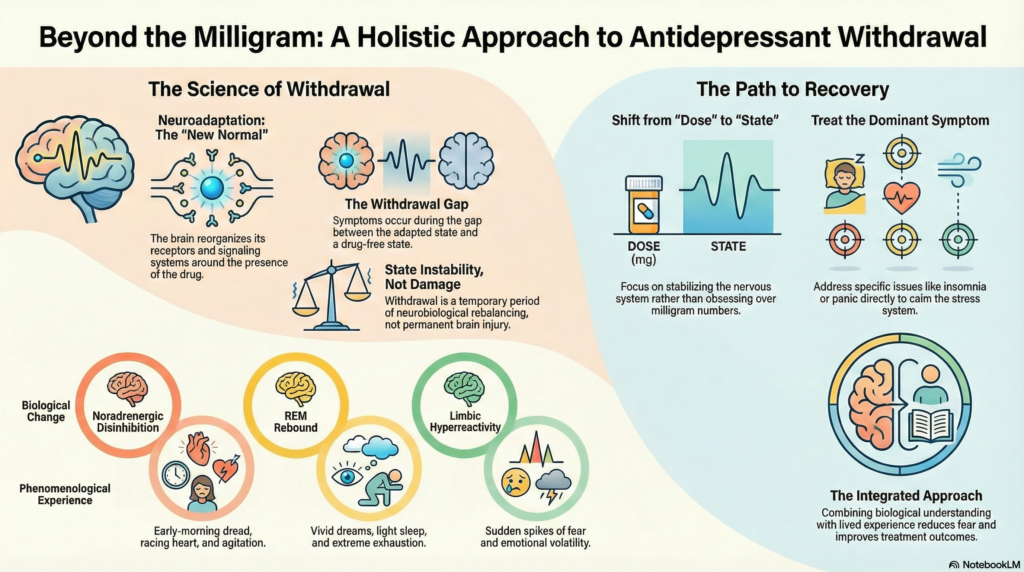

In other words, the brain reorganises itself around the presence of the drug.

This process is called neuroadaptation.

It is the same reason antidepressants take weeks to work —

and the same reason withdrawal exists.

Neuroadaptation: the key to both benefit and withdrawal

When antidepressants are taken long enough, the brain reaches a new equilibrium.

It recalibrates:

-

receptor numbers

-

neurotransmitter release

-

stress-circuit tone

-

emotional reactivity

This new balance becomes the brain’s new normal.

So when the drug is reduced or stopped, the brain is suddenly operating without the conditions it adapted to.

Withdrawal symptoms are simply the gap between:

-

the old adapted state

-

the new drug-free state

Withdrawal is not toxicity.

It is delayed neurobiological rebalancing.

The phenomenological story: what people actually feel

Neurobiology explains why withdrawal happens.

Phenomenology explains how it feels.

People do not experience withdrawal in receptor language.

They say things like:

-

“I feel wired but exhausted.”

-

“My sleep is completely broken.”

-

“My anxiety feels alien — not like before.”

-

“Tiny dose changes wreck me.”

-

“My emotions feel raw and unstable.”

These experiences are not side-notes.

They are the clinical reality.

Where biology and experience meet

These two lenses describe the same process from different angles.

For example:

-

Noradrenergic disinhibition → early-morning dread, racing heart, agitation

-

REM rebound → vivid dreams, light sleep, exhaustion

-

Limbic hyperreactivity → sudden fear spikes, emotional volatility

-

Sensitisation of stress circuits → worsening with both dose increases and decreases

When either side is ignored, treatment becomes distorted.

Why dose-only logic fails patients

If we think only in terms of receptors and dose curves, we ask one narrow question:

“Should we go up or down on the antidepressant?”

But many patients get worse with both.

That tells us the problem is no longer just the drug level.

It is the state the nervous system has shifted into.

Dose logic alone cannot describe that.

Why experience-only thinking also fails

If we think only in terms of lived suffering without biology, people conclude:

“My brain is permanently damaged.”

“Psychiatry has injured me.”

This creates hopelessness and blocks rational treatment.

Biology reminds us that:

-

brains adapt

-

brains destabilise

-

brains re-stabilise

Neuroplasticity cuts both ways.

The combined model: states, not just doses

The integrated view is simple.

Antidepressants shift the brain into a new functional state.

Withdrawal shifts the brain into another temporary functional state.

Some people move smoothly between states.

Some people destabilise and get stuck in a hyperaroused, sensitised state.

This explains why:

-

reinstatement sometimes helps

-

reinstatement sometimes worsens symptoms

The nervous system — not the milligram number — is now the main problem.

Return to phenomenology: how recovery actually happens

When tapering goes badly, the most important move is not another dose change.

It is returning to phenomenology.

That means asking:

-

What symptom is dominant right now?

-

Is it insomnia?

-

Is it hyperarousal?

-

Is it panic?

-

Is it depression?

Then treating that symptom directly.

For example:

-

dominant insomnia → stabilise sleep

-

dominant hyperarousal → calm the stress system

-

dominant panic → reduce threat-prediction loops

-

dominant depression → treat depression as depression

This shifts treatment from:

“dose management” → “state stabilisation”

The most important principle

The cause of suffering is not always what is maintaining it.

Withdrawal may have triggered the crisis.

But insomnia, fear, hyperarousal, and sensitisation may now be keeping it alive.

Those are all treatable.

Final message

Antidepressants are not magic chemicals.

They are state-shifting agents.

Withdrawal is not brain damage.

It is state instability.

Recovery does not come from obsessing over milligrams.

It comes from:

-

understanding the biology

-

listening to lived experience

-

treating dominant symptoms

-

reducing fear

-

allowing time for re-stabilisation

Good psychiatry lives at the intersection of neurobiology and phenomenology.

About the Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall), Chennai

Dr. Srinivas specialises in the personalised treatment of anxiety and depression, antidepressant optimisation, safe deprescribing, and the management of difficult medication withdrawal states.

His clinical approach integrates modern neurobiology with careful phenomenology — treating not just diagnoses or drug doses, but the actual state of the nervous system.

He has guided thousands of patients through medication transitions using a calm, evidence-based, and non-dogmatic framework that prioritises sleep stabilisation, fear reduction, and symptom-targeted care rather than rigid tapering protocols.

Areas of special interest

-

Antidepressant and benzodiazepine deprescribing

-

Treatment-resistant anxiety and depression

-

Neurofeedback-assisted stabilisation

-

Sleep and circadian rhythm disorders

-

Panic disorder and autonomic dysregulation

-

Cognitive and emotional symptoms in long-term antidepressant users

If you are struggling to stop an antidepressant, feeling worse during tapering, or confused about whether your symptoms are withdrawal or relapse, a structured clinical evaluation can bring clarity and relief.

📍 Mind & Memory Clinic

Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall), Chennai

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com

📞 +91-8595155808