Why QEEG Has Not Yet Picked Up in Psychiatry

Quantitative EEG (QEEG) seems, on paper, like it should have become a natural ally of psychiatry.

It measures brain function. Psychiatry treats disorders of brain function.

And yet, decades after its introduction, QEEG remains peripheral—used by a minority of clinicians, often viewed with suspicion, and rarely embedded in mainstream psychiatric workflows.

This is not because QEEG lacks relevance to psychiatry.

It is because psychiatry, as a discipline, sits at a unique intersection of biology, subjectivity, culture, and care systems—and QEEG fits that intersection awkwardly.

1. Psychiatry already struggles with biological reductionism

Modern psychiatry carries historical baggage.

Every few decades, a new “biological breakthrough” arrives promising:

-

objective diagnosis

-

definitive biomarkers

-

clean separation of disorders

EEG itself once carried that promise. So did neuroimaging. So did genetics.

Psychiatrists learned—sometimes painfully—that mental illness cannot be reduced to a single biological readout. Suffering is embedded in development, relationships, meaning, and context.

QEEG, when presented as a brain-based explanation, inadvertently triggers this old anxiety:

“Is this another attempt to oversimplify the mind?”

As a result, many psychiatrists react defensively—not because QEEG is wrong, but because psychiatry has learned to distrust claims of biological finality.

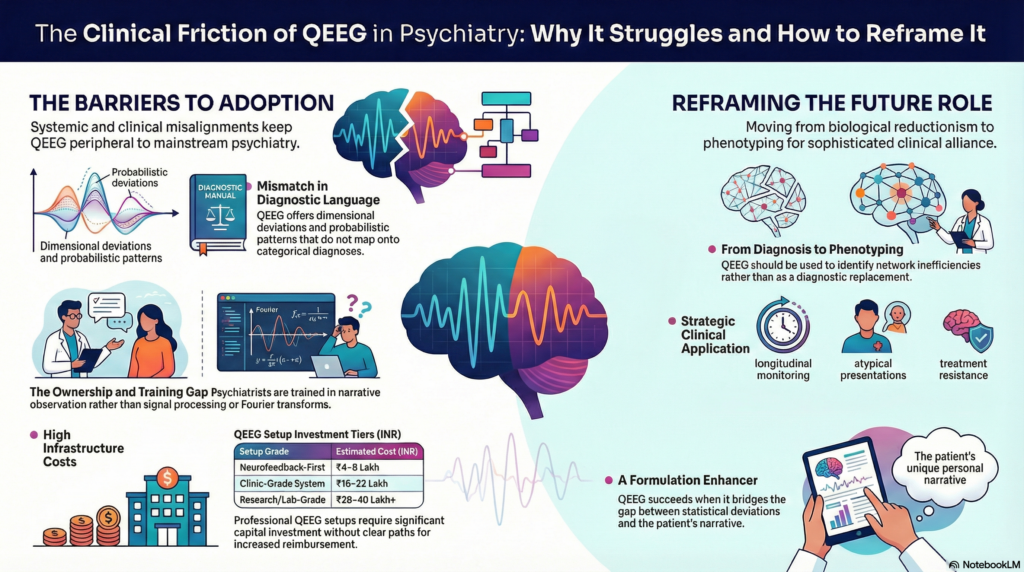

2. QEEG does not speak the language of diagnosis

Psychiatry works with categorical diagnoses:

-

Major Depressive Disorder

-

ADHD

-

Schizophrenia

-

Bipolar Disorder

QEEG does not naturally map onto these categories.

Instead, it offers:

-

dimensional deviations

-

probabilistic patterns

-

overlapping signatures

A frontal alpha asymmetry may be associated with depression—but it is not depression.

Theta excess may be seen in ADHD—but also in trauma, sleep deprivation, or medication effects.

This creates discomfort.

Psychiatry is already criticised for diagnostic ambiguity.

QEEG adds another layer of nuance rather than resolving it.

Clinicians ask, reasonably:

“How does this change my diagnosis or treatment decision today?”

Often, the answer is indirect, not immediate—and indirect tools struggle to survive in busy clinical practice.

3. Training gaps: QEEG sits outside psychiatric education

Most psychiatrists are trained to:

-

interview

-

observe

-

formulate

-

prescribe

-

psychotherapeutically engage

They are not trained in:

-

signal processing

-

Fourier transforms

-

coherence matrices

-

Z-score interpretation

As a result, QEEG appears:

-

technically intimidating

-

interpretively opaque

-

dependent on external experts

When a tool cannot be owned intellectually by the clinician, it rarely becomes routine.

Neurologists own EEG.

Radiologists own imaging.

Psychiatrists, by and large, do not own QEEG.

Without ownership, uptake stalls.

4. The economic mismatch with psychiatric practice

Psychiatric services are relatively low on capital expenditure.

A psychiatrist can run a full OPD with:

-

a consultation room

-

time

-

training

By contrast, serious QEEG infrastructure is expensive, especially when done properly.

In India (net landed costs):

-

Affordable neurofeedback-first setups: ₹4–8 lakh

-

Clinic-grade QEEG systems: ₹16–22 lakh

-

Research / lab-grade systems: ₹28–40 lakh+

For hospital administrators, the question becomes blunt:

“Why invest in QEEG when it does not clearly increase throughput or reimbursement?”

Unlike imaging or procedures, QEEG:

-

is time-intensive

-

is poorly reimbursed

-

depends on interpretation rather than automation

Psychiatry already struggles with monetisation. QEEG adds cost without an obvious billing pathway.

5. Psychiatry values narrative; QEEG values statistics

Psychiatric understanding is narrative-driven:

-

life history

-

personality structure

-

meaning-making

-

interpersonal patterns

QEEG outputs are statistical:

-

deviations

-

correlations

-

distributions

These are not competing truths, but they live in different cognitive worlds.

When QEEG reports are presented without integration—without translation into clinical language—they feel alien, even irrelevant.

A psychiatrist does not ask:

“Is this Z-score abnormal?”

They ask:

“How does this help me understand this person?”

When QEEG fails to bridge that gap, it gets quietly set aside.

6. The damage done by overclaim and misuse

QEEG has also been harmed by its own misuse in psychiatry.

Over the years, some practitioners have claimed:

-

QEEG can diagnose psychiatric disorders

-

specific colour patterns prove conditions

-

brain maps can replace clinical assessment

These claims are scientifically indefensible.

Mainstream psychiatry, rightly cautious, responded by discarding the tool rather than correcting its use.

Unfortunately, scepticism does not discriminate well between:

-

misuse of QEEG

-

QEEG itself

The baby was often thrown out with the bathwater.

7. Medication-driven psychiatry reduced the perceived need

Modern psychiatry—especially in resource-limited settings—became medication-centric.

SSRIs, antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, stimulants:

-

are effective

-

are scalable

-

fit existing systems

QEEG does not easily inform:

-

first-line prescribing

-

rapid medication decisions

Its strengths lie elsewhere:

-

treatment resistance

-

atypical presentations

-

neurodevelopmental complexity

-

neurofeedback planning

But these are second-order problems—and systems are rarely built around second-order thinking.

8. Why QEEG may still matter deeply to psychiatry

Despite all this, QEEG has not disappeared. And that itself is telling.

QEEG persists because psychiatry increasingly encounters:

-

partial responders

-

chronicity despite guidelines

-

overlapping syndromes

-

patients asking for “objective explanations”

In these spaces, traditional models strain.

QEEG does not offer diagnosis.

It offers phenotyping.

It helps psychiatry ask better questions:

-

Which networks are inefficient?

-

Is this under-arousal or over-control?

-

Is the problem one of integration rather than intensity?

-

Is treatment changing brain function or only symptoms?

These are psychiatric questions—just framed differently.

9. A reframing psychiatry can live with

QEEG has not picked up because it was often positioned wrongly.

It does not belong as:

-

a diagnostic replacement

-

a screening tool

-

a routine investigation

It belongs as:

-

an advanced assessment

-

a formulation enhancer

-

a neurofeedback guide

-

a longitudinal monitoring tool

When QEEG is used selectively, ethically, and interpretively, it complements psychiatry rather than threatening it.

Conclusion

QEEG did not fail psychiatry.

Psychiatry simply did not have a place ready for it.

Not because psychiatry is anti-biology—but because it understands, perhaps better than most fields, that the brain is not the whole story.

QEEG will never replace clinical judgment.

But in a discipline increasingly asked to be precise, accountable, and evidence-informed, it may yet find its role—not as a revolution, but as a quiet, sophisticated ally.

Author

Dr. Srinivas Rajkumar T, MD (AIIMS), DNB, MBA (BITS Pilani)

Consultant Psychiatrist & Neurofeedback Specialist

Mind & Memory Clinic, Apollo Clinic Velachery (Opp. Phoenix Mall)

✉ srinivasaiims@gmail.com 📞 +91-8595155808

Psychiatry advances not by choosing between brain and mind—but by learning to hold both, without reduction or denial.